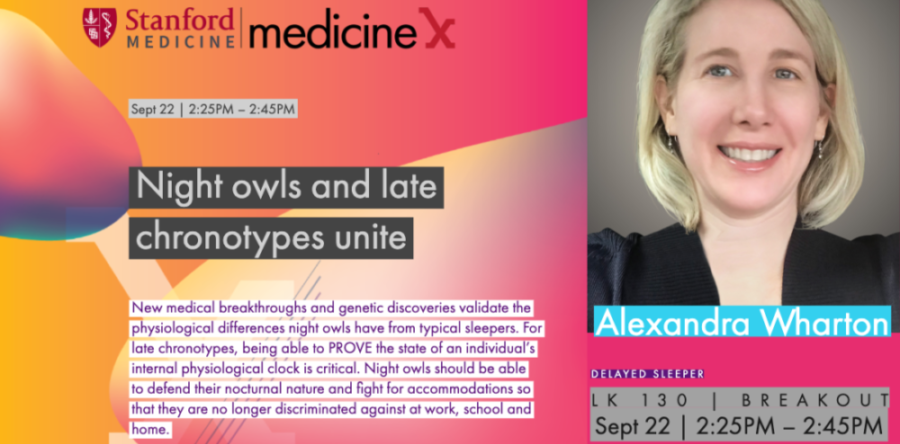

At the Stanford Medicine X conference in September, I gave a talk titled 'Night Owls and Late Chronotypes Unite — Let's Stop Living Against Our Body Clocks.'

I explained what Delayed Sleep Phase Disorder is, the challenges of diagnosing it, and its possible causes including recently discovered genetic variants. Attendees learned that the 2017 Nobel Prize for Medicine was awarded to scientists studying the circadian clock, and that research in how a person's circadian clock affects their physical and mental health is growing.

I stressed that DSPD is intractable and can't be adjusted with willpower or self-discipline; it's a physiological - not a psychological - condition. I described how living against one's body clock is damaging, and that later start times at work and school are imperative for late chronotypes.

The session had a rapt audience of healthcare providers, researchers and patients, and the level of discourse was encouraging. There was a discussion following the presentation about how DSPD is frequently mistreated: SSRIs can make night owls more sensitive to light, phase-delay chronotherapy can turn DSPD into Non-24, and long-term benzodiazepine use is dangerous.

The theme of this year's Medicine X conference, 'Listening to Patient Voices Drives Change in Healthcare,' aligns with CSD-N's tagline, 'Together We Have A Voice.' CSD-N's successful letter-writing campaign asking the NIH to include circadian rhythm disorders in its list of sleep disorders exemplifies how a community of patients can bring about change.